Anatomy of a Caller Line ID Spoofed Vishing Attack

Following on from a couple of Twitter conversations and as a result of this thread I thought a deeper dive into how this works (at least more than 280 characters, anyway), and how people can protect themselves from this type of scam.

There seems to be an assumption that this type of attack is complicated to perform, but it’s relatively trivial - all that is needed is a SIP trunk provider that don’t carry out checks to ensure number ownership and/or a previously compromised phone system owned by a legitimate business to proxy the calls through who use one of those providers (if you run a SIP gateway, you’ll be very used to logs showing attempted compromise through brute forcing using SIPVicious)

I know a lot of people have got into the habit of checking numbers against a providers website, but I don’t believe that the message has got through with the updated advice from Barclays (https://www.barclays.co.uk/digisafe/phone-number-checker/) and many others that this doesn’t provide protection against criminals who are actively spoofing numbers.

How does the attack work?

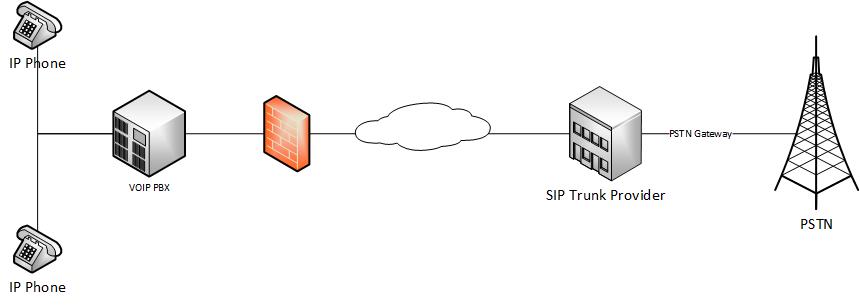

First of all it’s important to know how SIP Trunking works. A business/consumer will rent a trunk from a carrier in the same way as you would historically get a phone line on the PSTN (Public Switched Telephone Network), however rather than that line physically terminating at your premises, you either notify the trunk provider of your IP address for authentication purposes, or are assigned a username and password to authenticate against the trunk. The phone system is then connected over the internet to the provider, and the provider acts like a bridge between the PSTN and the VoIP phone system.

As part of this rental agreement, you’re also assigned either a single or range of direct dial numbers. This is where legitimate functionality can be abused. When making outbound calls a phone system has the capacity to set a series of SIP parameters in the headers. For example, you might want to specify different outbound CLI’s for different extensions in your dialplans (your Marketing Department might want to have a different direct dial to your Finance Team), or a different office that is carried on a separate SIP trunk. Maybe as a business you outsource certain outbound Sales activities, but want inbound calls to be routed back to you directly.

To take the example of different departments advertising their own CLI, on Asterisk, this would look like:

exten => _X,2100,1,Set(CALLERID(all)="Marketing"<02031234567>)

exten => _X,2102,1,Set(CALLERID(all)="Finance"<02031234568>)

Some providers offer a feature called “CLIP no screening”. When this is activated with the SIP carrier the user provided CLID is accepted and sent on to the PSTN network - this is potentially dangerous. The same phone system could send:

exten => _X.,2101,1,Set(CALLERID(all)="Marketing"<02031234567>)

exten => _X.,2102,1,Set(CALLERID(all)="Finance"<02031234568>)

exten => _X.,2103,1,Set(CALLERID(all)="Barclays"<03457345345>

..and pretend to be placing a call from the Barclays Fraud prevention team, as happened in the example above. Without screening the provider is “trusting” the person making the call to be honest about their number.

Some providers are making valid efforts to make sure that this kind of fraud cannot take place on their networks by stripping the “user provided header” if it doesn’t match the DDI range that has been assigned to a trunk and replacing with the “network provided header”. Carriers such as Zen use P-Asserted Identity tags to validate that the authenticated client has the right to use the CLI that they wish to advertise.

Others, however appear to be turning a blind eye to this behaviour or not implementing some of the controls that are available. It’s simple to search for carriers that advertise “CLIP no screening” as a feature (and on writing this one PBX provider actually lists some of these carriers on their website).

Why does this problem exist?

As with a lot of internet services, security has sometimes been an afterthought in the design. The original SIP standard was defined in 1999 (https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc2543) and as with many of the early drafts of internet protocols, the design focused primarily on making things work, rather than exploring the potential for abuse. The problems with the current way SIP works are shown in https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7340 and there have been subsequent RFC’s suggesting solutions to these problems. Designing and ratifying standards is a slow process though, and then carriers and PBX providers actually need to adopt the standards, all while not breaking existing functionality. SIP is a complex protocol - you just need to look at the permitted parameters to get an idea of how challenging it would be to remove features that many users legitimately rely on: https://www.iana.org/assignments/sip-parameters/sip-parameters.xhtml

How can the issue be solved?

Work is being done in this field on a technical level, and there’s no doubt that greater collaboration between telecoms companies and SIP carriers will help over time. In order to apply technical controls though as global effort is needed to force SIP trunk providers to all adhere to the regulations - which is unlikely. For now banks and corporations need to get the message to their customers that it’s not sufficient to check a website to make sure the number calling you is valid - this isn’t a true method of verification. If you receive a call that you’re not expecting and they want you to disclose potentially risky information, always hang up the call and ring back.

UPDATE - Nov 2023

Short update to this, as serious progress has been made in the implementation and adoption of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/STIR/SHAKEN, at least in the USA with Ofcom in the UK making this a regulatory requirement by https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0029/260678/shockey-report-issues-with-cli-authentication.pdf.