Inside a Microsoft Tech Support Scam

This is a slightly unusual post for me, as I can actually discuss an incident in depth without being bound by an NDA. Also unusual as this is a scam affecting domestic users, most of whom don’t have a budget to perform full incident response and therefore I don’t often see, but may provide some insights into the tools, techniques and procedures used in a Microsoft Tech Support Scam.

I received a call from my in-laws, who I’d describe as pretty street-smart. However, as they’re both in their mid to late 70s and didn’t grow up with technology, they’ve had to learn as they’ve gone along.

My father-in-law described the incident as follows (although I’m slightly paraphrasing):

“I was browsing the web and trying to book a session at the local climbing wall, when a popup appeared on my screen that advised that his PC was infected with a virus, and to call Microsoft. I called a tech support advisor on the number on the screen, and they told me to install something, and then they started doing things with the computer. I was watching them, but became concerned when they “disabled McAfee”. I ended the call, powered off the laptop and called you. “

Naturally, I offered to check out the laptop for signs of infection, but was also interested what had happened. I advised them to rotate all credentials that might have been used on the laptop (email, Amazon, banking, Facebook, etc) - thankfully the device is infrequently used, and they don’t have a huge online presence or footprint.

Investigation

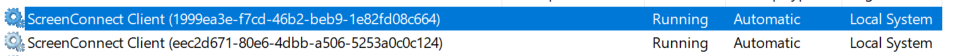

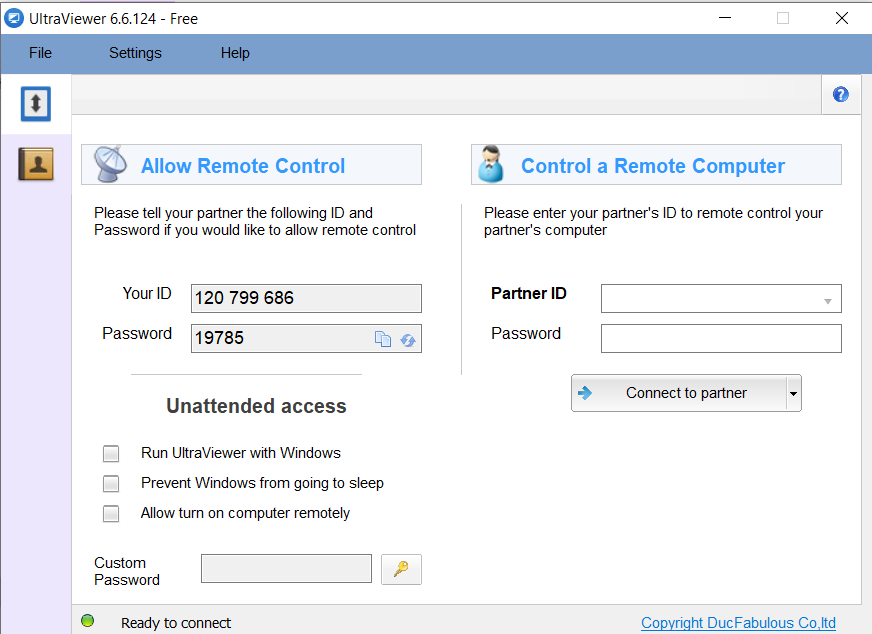

As there was no risk of affecting chain-of-custody - there’s no insurance or criminal proceedings at play here, and also as I had quite a busy week, I dropped the machine into an isolated VLAN in the lab with no internet access, powered on, grabbed a disk image using FTK and grabbed a memory dump, and then sadly had to park this for a few days. I performed a cursory check of running processes, and noted that there were 2 Screenconnect sessions running as services, and Ultraviewer - but as the laptop was restricted from accessing the internet and on an isolated network, there was no risk associated with the device talking back.

I was conscious that memory forensics were unlikely to return anything that disk forensics wouldn’t as the device had been fully shutdown - but my in-laws had done the right thing regardless.

At this stage, we knew the threat actors had “done things”, but had no knowledge of what tasks they had performed. We were confident that all stored credentials on the device had been quickly rotated though - so the risk to the end users was minimal.

Reviewing the Disk Image in Autopsy

This aspect of the investigation was sped up significantly by the fact that the device was very infrequently used, resulting in very limited logs or activity to review.

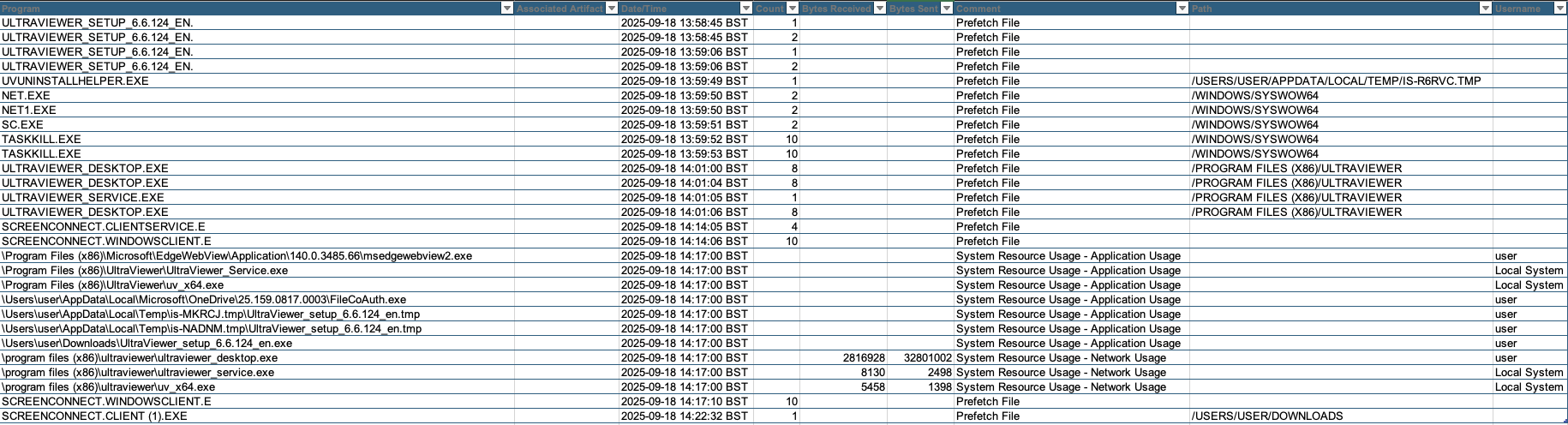

Building a timeline of application execution, notable items are shown below:

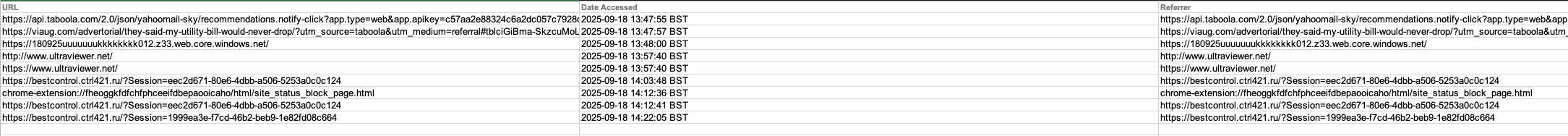

The next aspect to review was the web history:

This aligns with the program activity - and we can see what’s happened. My father-in-law had previously been Googling reviews for an electric drill, and presented with the usual plethora of ads while searching in Chrome and been caught by “malvertising” being served in amongst legitimate ads from Taboola. There are a number of articles online about this behaviour, such as this one from 8 years ago, and it appears the practice is still relatively common:

(An article on this point from Malwarebytes is worth a look)

Panicking when seeing the warning, and notably, checking the URL in the address bar appeared to be from Microsoft, as it’s using the web.core.windows.net domain, and showing as:

1491_Helpdesk_Support-W - https://180925uuuuuuukkkkkkkk012.z33.web.core.windows.net/

(The wisdom behind Microsoft using the .web.core.windows.net domain for end users to spin up VM’s and blob storage behind is obviously questionable - when Microsoft’s own domains themselves can be untrustworthy, it renders yet more security advice from the past invalid).

He did what he thought was right and called the number on the screen (which, for the record if anyone reading this wants to have any fun, is 0800 2062779).

Impact Assessment

The next step was to try to establish how badly my family had been compromised.

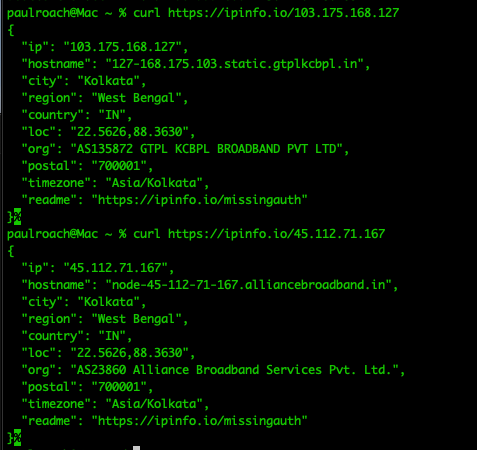

Initial access was achieved by getting my father-in-law to download and install Ultraviewer to grant access to the 3rd party - this tool helpfully does have some logging, and I’m assuming that the attackers would have purged this if their access hadn’t been revoked so suddenly. Connection logs helpfully gave us a couple of IP addresses and hostnames:

18/09/2025 14:03:15|113643413|DESKTOP-D7HUO3J|RandomPass|103.175.168.127 18/09/2025 14:15:57|115520960|DESKTOP-3V048DA|RandomPass|45.112.71.167

It appears the sole action taken through the Ultraviewer instance was to then install two further remote access instances, both ScreenConnect.

ScreenConnect is a legitimate, popular remote access tool created by ConnectWise - it’s designed for helpdesks to assist users with issues. It’s become popular with criminals though for a few reasons:

- It’s self-hosted - a criminal organisation can set this up on their own server anywhere in the world without risk of getting cut off as a result of an abuse claim

- As it’s self hosted, no third party will be retaining copies of logs relating to activity.

- It doesn’t log activity relating to connections or file transfers locally (either in its own or in the Windows Event Logs) beyond the time of the connection.

- It runs with “System” permissions, granting the fake helpdesk access to any files or folders on the end user machine, and granting consent to launch any applications remotely without additional consent being required. A remote shell means any activity carried out can happen without being visible to the user.

With limited knowledge of what files were transferred, the best course of action was to assume that any files or stored credentials on the laptop could have been compromised. Thankfully, only email credentials (which had already been changed), the password for my mother-in-law’s Railcard and the password for the local climbing wall were stored. The only files of note were draft copies of the local village magazine which my mother-in-law edits - none of which would be much use to the scammers. It warms my heart a little to know that so much effort was expended by these criminals for so little gain.

Digging a Little Deeper

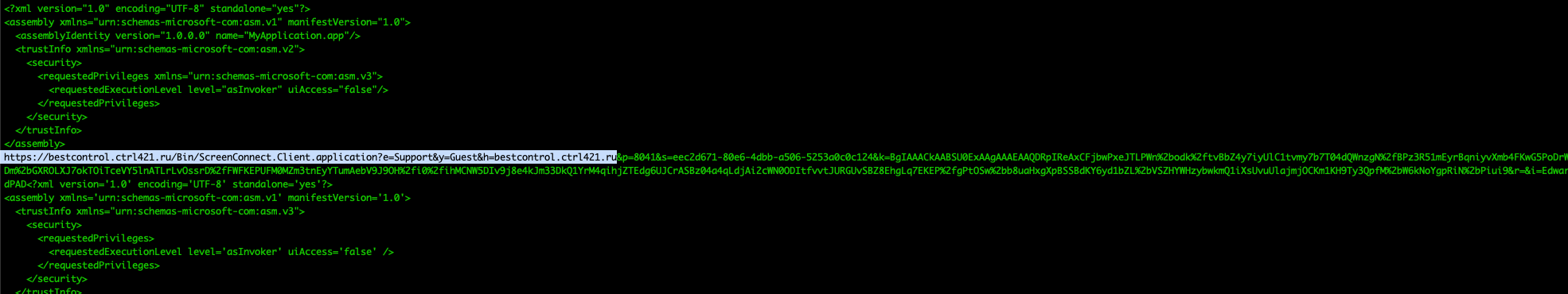

We already have a couple of known IPs from the UltraViewer installation, but both ScreenConnect instances were installed without any additional parameters. In order for it to know where to talk home to, then parameters must be included in the executable. Enter “strings”:

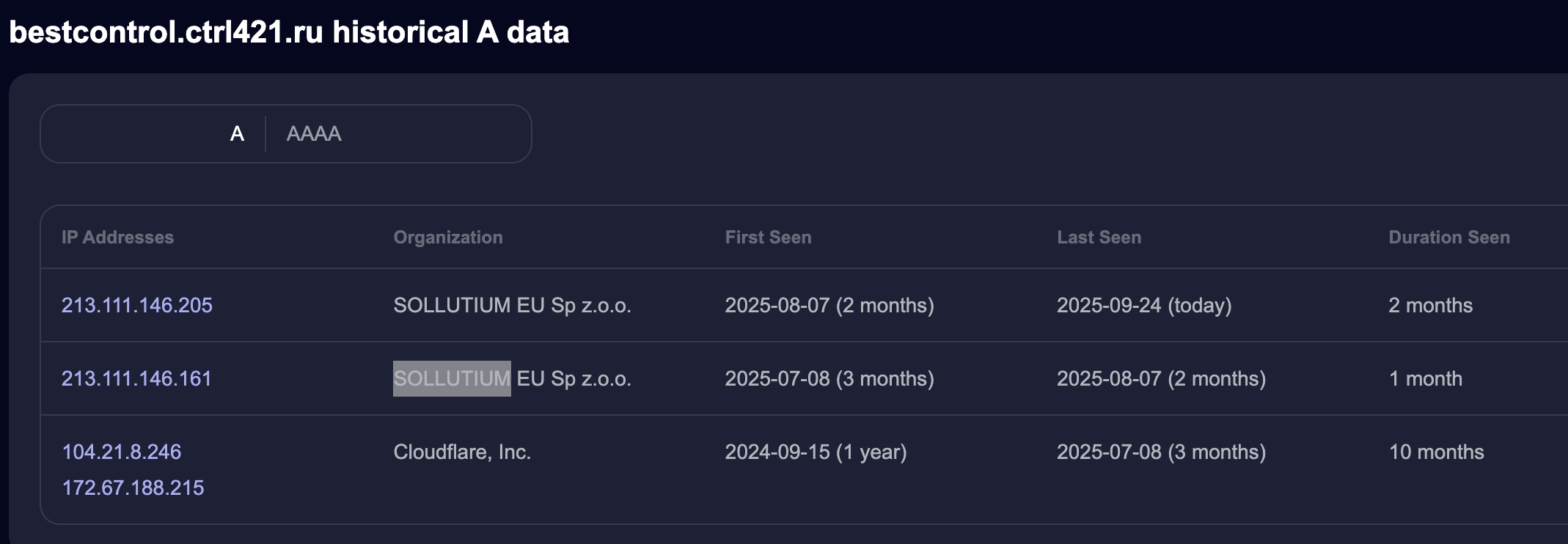

We have a domain for the first ScreenConnect installer that was launched of hxxp://bestcontrol.ctrl421.ru

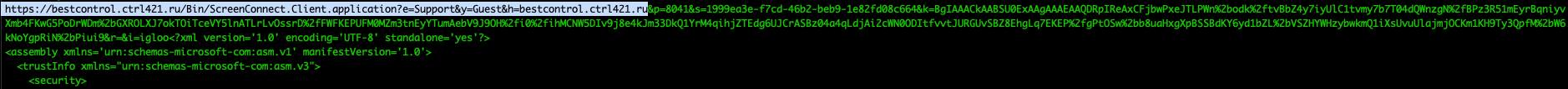

I verified that both of the domains used were the same - as it’s common for C2 frameworks to use multiple IP’s to prevent getting locked out, but it appears these scammers don’t have that level of sophistication:

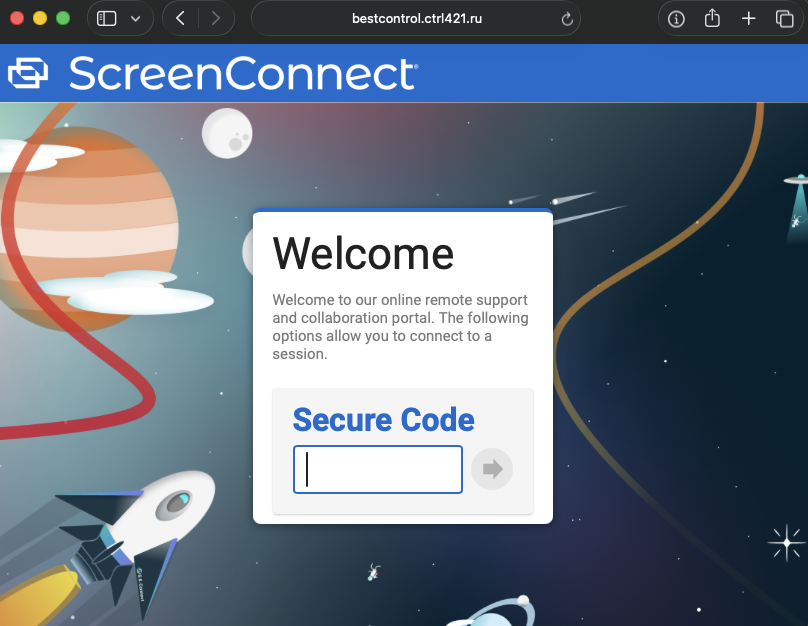

We can also confirm the domain is still active:

At time of writing, this bestcontrol.ctrl421.ru resolves to 213.111.146.205 where the ScreenConnect server is hosted.

A quick look at this server reveals that it’s listening on 80 for a redirect, 443 and more unusually 5986, the TLS certificate for which shows Cloudbase-Init WinRM which tells us a little about the method this provider uses for provisioning of their servers: https://cloudbase-init.readthedocs.io/en/latest/intro.html.

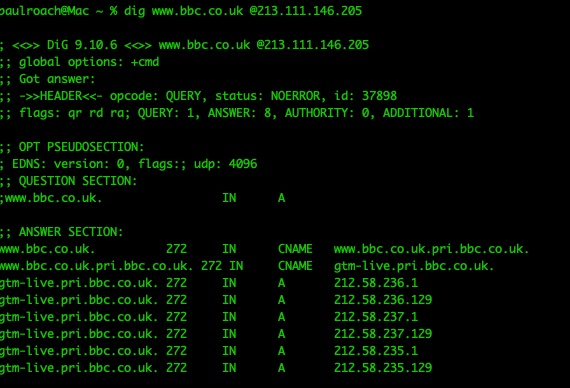

It also appears to be running an open DNS forwarder/resolver, which implies either misconfiguration or another service the scammers are using:

Notably, this domain was previously masked by Cloudflare, before migrating to a different SOLLUTIUM host before locating on this one in August of this year:

The 2 other IP’s of interest resolve to 2 separate ISP’s in India:

The first host: 103.175.168.127 is not listening for traffic on any ports. The second (45.112.71.167), however is running the same version of DNS resolver as the hosting platform in Holland (NLnet Labs NSD) and freenginx (https://freenginx.org/en/), which can be used to redirect traffic based on specific patterns, and may be used as part of the campaigns the threat actors are conducting.

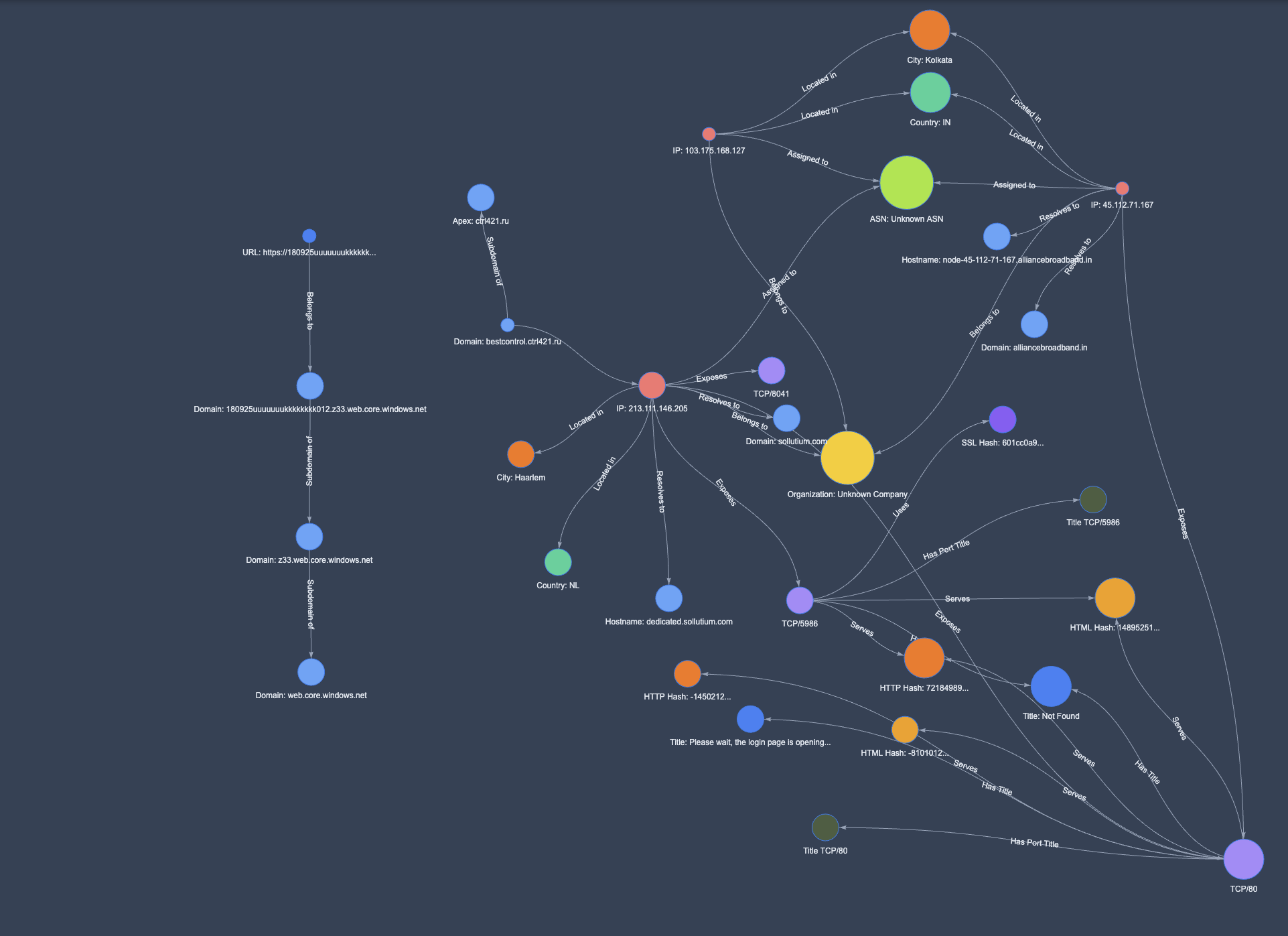

At this point, it’s probably quite difficult to visualise the data points.

Thankfully Dan vibe coded a nice, free, basic mapping tool that helps:

Post Investigation Cleanup

After completing malware scans and having a reasonable level of confidence that the only installed applications were ScreenConnect and Ultraviewer, and that all evidential artifacts have been collected and retained, the next step is to ensure that there’s no secondary risk of infection or anything that hasn’t been detected by AV.

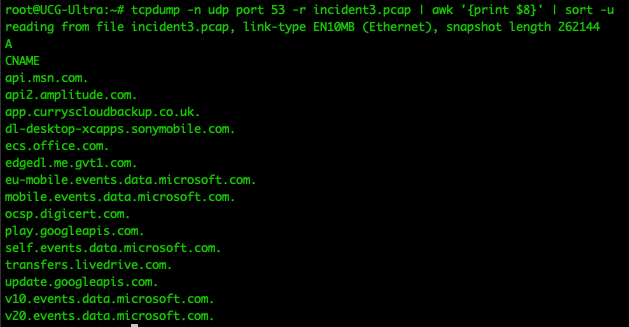

A quick check of startup items, browser extension and and scheduled tasks don’t reveal anything malicious - and running processes checked through Velociraptor don’t indicate anything either. To be sure, a long pcap is collected when the workstation is connected back to the internet. Most C2 frameworks will regularly beacon. A quick manual review of this can be performed (note that I ran the pcap from the gateway to my lab, a Ubiquiti Unifi UCG-Ultra):

tcpdump -n udp port 53 -r incident2.pcap

To view DNS requests, we only need the 8th column, so we can use awk and sort to view streamlined output:

A similar principle can be applied to IP traffic using tshark this time to pull an IP list:

tshark -qnz conv,ip -r incident2.pcap | awk '{print $1}' | sort -u

After a bit of cleaning, we can then check the IP List for anything that immediately stands out:

for i in $(cat iplist1.txt); do curl https://ipinfo.io/"$i"; printf "\n"; sleep 3; done

Once this list has been further filtered for known good IP’s, a batch lookup using Maxmind’s “Insights” lookups can provide further enrichment, allowing us to filter out known CDN’s for example. Maxmind’s Insights lookups aren’t free - so it’s recommended to de-duplicate and filter out known good IP’s before uploading.

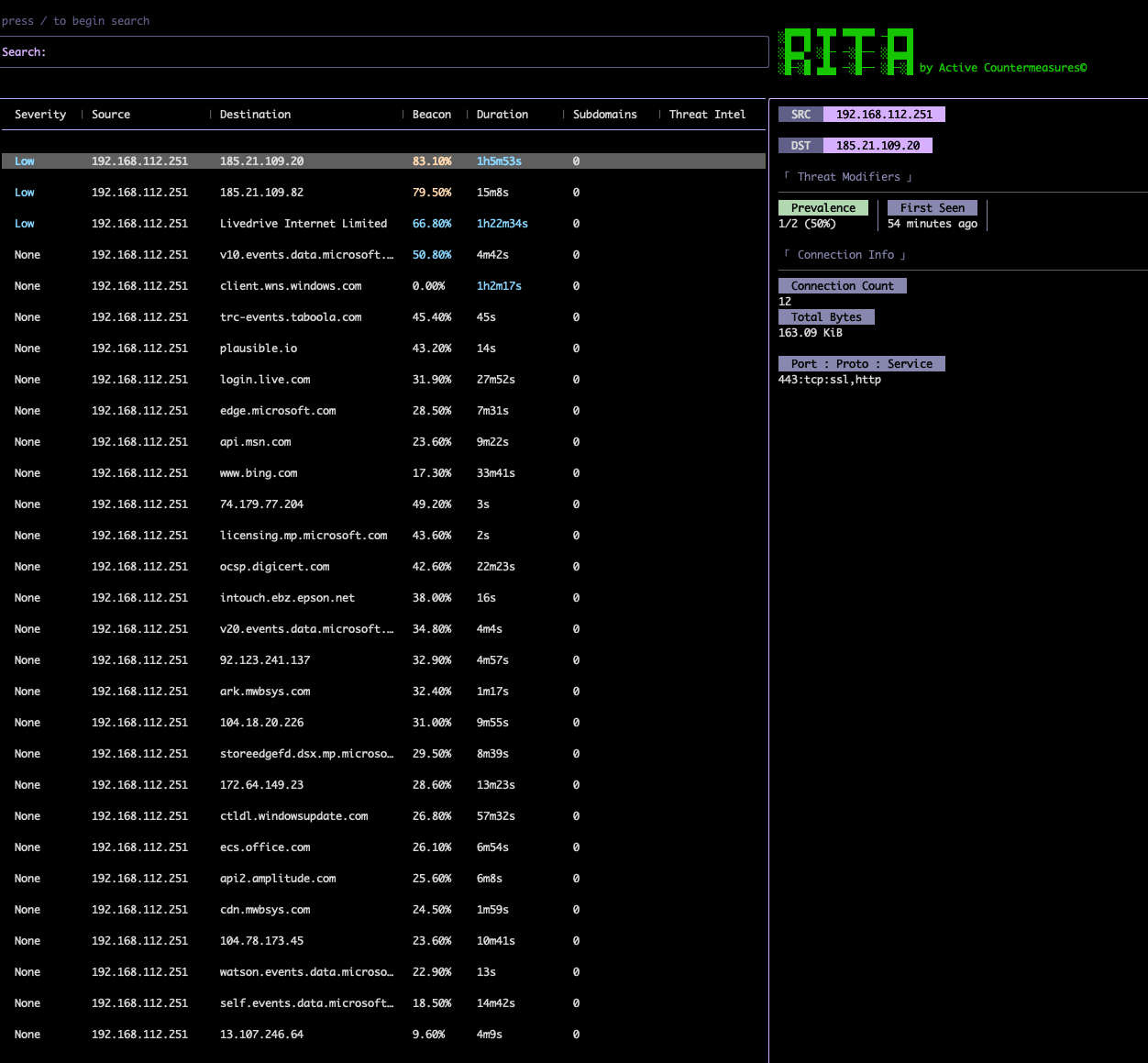

This data can then be referenced against packet captures filtered through Zeek & RITA to find a little more information about any active connections and to detect any C2 beacons through searching for uniform traffic patterns:

After checking this via a long packet capture we can have high confidence that no resident infection exists on the machine.

Conclusion It’s difficult to say with certainty what the endgame was for the criminals in this instance - whether they were interrupted/disconnected before dropping malware, whether they managed to exfiltrate credentials and session tokens from the workstation before being evicted or whether they were engaged in a scam whereby further “scareware” was to be installed before charging a fee to remove it.

It would be interesting to find out more though, so may be worth a call to their “support desk”, armed with a VM logging all activity to EDR, TLS inspection (https://www.netresec.com/?page=PolarProxy), and a few tasty canaries to see what the endgame was for the scam.